A little bit about this week’s episode

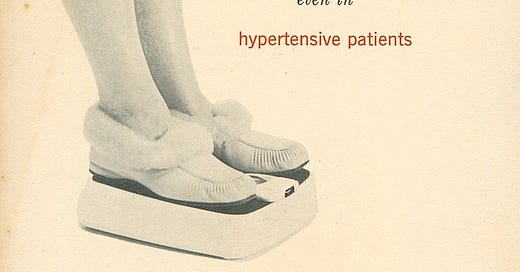

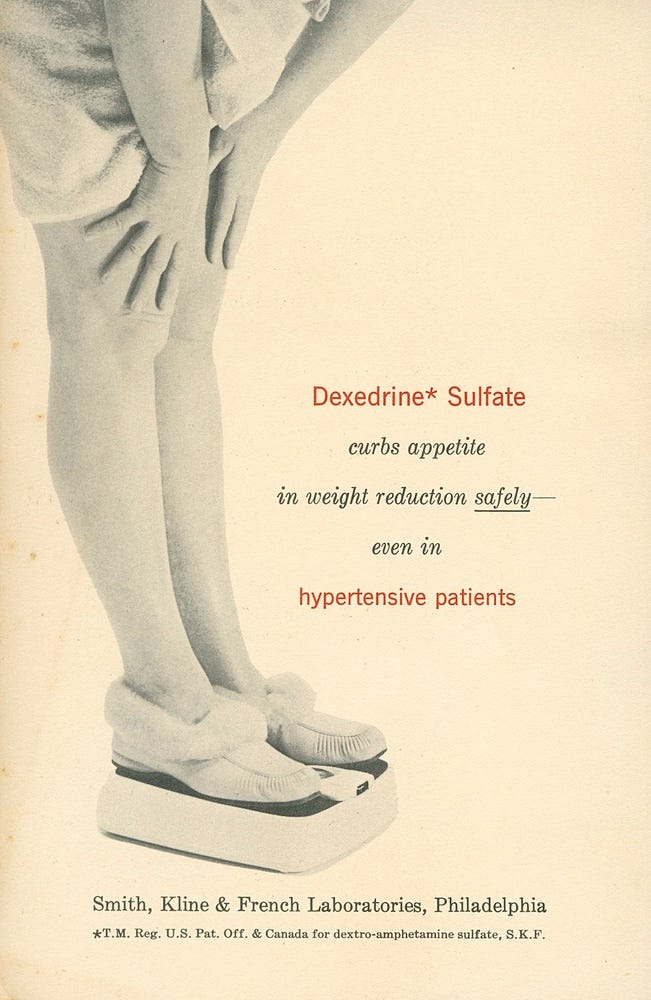

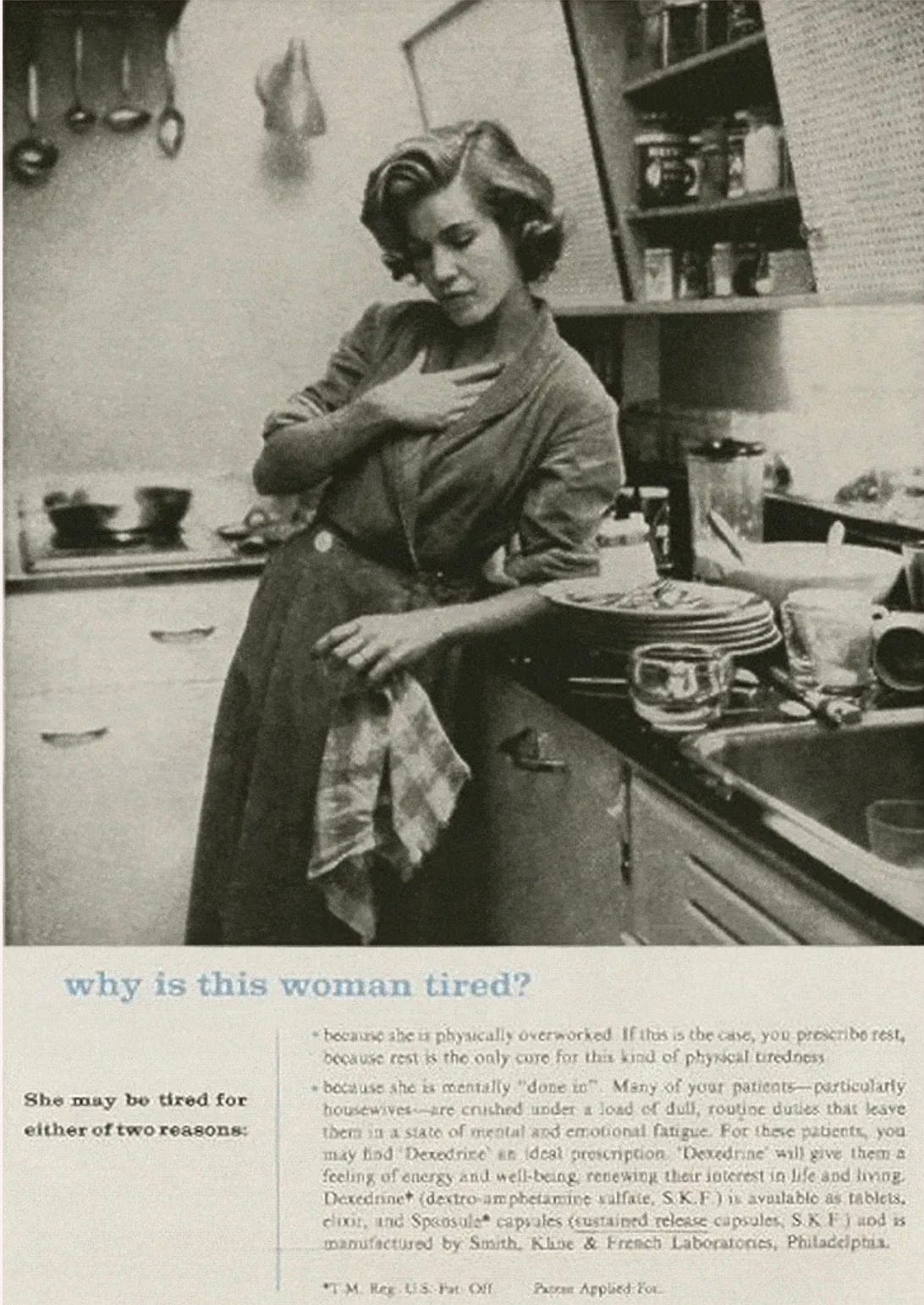

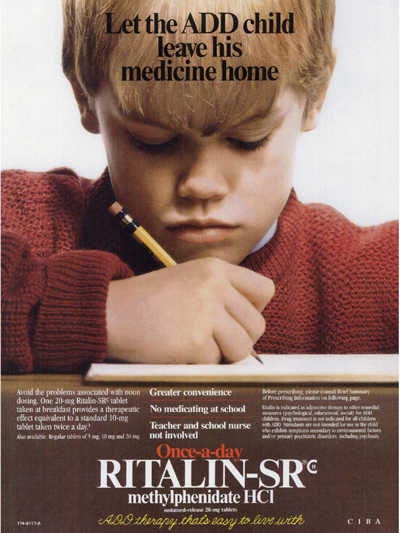

This week, a story about a question I’ve been grappling with for a while, and that honestly, I expect I’ll grapple with for a while after this. Why did I take speed for twenty years? A story of amphetamine's birth, life, death, and rebirth in America. (Methylphenidates, too.)

When I started trying to answer this question, I didn’t intend to talk about it in public. It really was just an actual question, in my own life, that took on some urgency a while ago.

Back then, I’d abruptly stopped taking a medication I’d spent more of my life on than off, and was surprised to discover that not taking the drug felt like its own kind of drug experience.

I found myself inhabiting a slightly different brain, with a slightly different way of perceiving the world. I don’t think there’s a word for someone who goes off of a prescription medication. You don’t become sober, but I did feel acutely like I’d gone from one state to another, without being able to really explain or name either state.

I’d love for people to share their personal stories in the comments. Or send me an email.

I expect listeners to feel strongly because the decision to take these medications, for anyone, and particularly for anyone with kids, is just such a big one. And because the people who benefit from these medications find them to be so helpful, sometimes even life-changing.

I also know that these people sometimes face stigma, and I don’t want to add to that stigma.

To just state my point of view on all this: if prescription medications help people, they should take them.

If I have a complaint with our system, it’s that in my experience, a prescription is often the end of a conversation instead of the beginning. I’ve found it’s rare to meet a doctor who ever suggests re-evaluating medication, even though our brains and the contexts we find our brains in, often change.

I don’t have answers for anyone but myself. I’ve been a zealot for and against these drugs and now I find myself closer to the middle. I’d ask that anyone wanting to discuss all this try to be civil and polite. By all means share your questions and experiences, but please try to be curious and respectful of other people’s too. Let’s not try to change each other’s minds in a comments section.

I usually read all the comments and emails people send, but I’ll probably take a minute before I do that this time.

Next week we’ll share the second part of this story, which approaches the same topic from a very different perspective, and arrives at different answers about ADHD and prescription stimulants.

A little bit about a story I wrote 8 years ago

Eight years ago, I published this audio piece that I still sometimes get nice emails about. It was called What It Looks Like.

Back then, I was working through some questions I had about depression. I’d had a friend I really loved who had died by suicide early in our lives. Her absence had left a real mark on me. And for the next decade, I found myself badly wanting to understand her experience of depression, this place I felt I’d lost her to. But the irony was, I was also experiencing it. I just didn’t really know it. This is from the piece:

For most of my twenties, I thought about killing myself. Often. Had I told anybody, they would have told me that that was a symptom of depression. But I never made that connection. I was hunting this thing that had taken my friend away, depression, and I was wondering what it looked like, how I could understand it, completely unaware that it was in me. For all that time, I just thought that everyone’s brain was like that. The same way I genuinely can’t imagine that anyone doesn’t always kind of want to be eating potato chips, I also just thought that anybody’s brain, faced with a sufficiently difficult problem, would suggest that one easy solution would be just dying. I just figured people learned to ignore that voice, no matter how insistent it got, no matter how loud. And then a friend of mine gently suggested that this was actually unusual, and I got a therapist, and I got medication, and now that does seem unusual. It seems hard to imagine. Which is really nice.

The piece landed on that moment of irony. The idea was that I had been like Ahab hunting for Moby Dick, not realizing the boat he’s on is actually a large whale in a boat costume.

The nice emails I get about that piece are from people who got help because they heard my description of my own depression and realized it applied to them, too. Those are really rewarding messages to read.

But these days I feel much more conflicted about writing about mental health. And that piece is part of the reason why. The demands most stories make — a clear ending, a resolution — I think those are exactly the pitfalls I’ve learned to be wary of when it comes to managing my own mind.

I wrote the end of that story when I was 29. To my ear, it goes — “I was depressed, but I got medication, and now everything’s fine.” If that was true then, it didn’t stay that way. Medication helped me with depression for some time, and then, it didn’t.

At 29, I did not know that I had more challenging mental health troubles ahead. And when those troubles showed up, I felt stupid for having written about my own mental health like it was a troubleshooting issue I’d solved with a software patch. The ending felt glib, but there wasn’t much I could do about it.

So, consider this a very late correction. Life continued to provide challenges and moments of beauty. I expect that to continue, but if it changes, maybe I’ll feel inspired to write an update for you.

Thanks for indulging me, and we’ll see you next week with a new one.

I am so sorry to hear about your mental health challenges, and I admire you for your wisdom in knowing that they are a lifelong condition.

Our family’s amphetamine story concerns our son. He started taking Adderall at age 8, because his autism made it difficult for him to focus on topics that didn’t interest him in school. I was very reluctant to start him on meds, but his pediatrician said, “why would you want to risk having him hate school?” So I agreed--but my husband and I decided to do an n = 1 study to see if he really needed the medication. In both second grade and third grade, we picked a two-week period and told his teachers that during those weeks, every morning we would flip a coin, and if it was heads, he’d get the pill, and if tails he wouldn’t. We asked that they tell us every day whether they thought he had had the pill or not. Both teachers got it right 100 percent of the time, and both said that it wasn’t at all ambiguous--they could tell within minutes whether he was on the meds or not. That was good enough for me, so we kept him on. We gave him the Adderall (and later Vyvanse and Concerta) on school days only, until he graduated from high school.

He went to college in the UK, where take courses in your subject only; you don’t take general education (i.e. not math, science, or foreign languages--subjects that didn’t interest our son). He didn’t like how the meds made him feel, so he went off them. Because he was only required to study topics that interested him in college, he didn’t need the meds to help him focus and was very successful without them.

The upshot, in my opinion and based on our family’s experience, is that these meds can help make school an easier and more pleasant experience for kids who struggle with focus, and that is good. There are people with ADHD who will benefit from these meds during and after school. But perhaps we also ought to think about ways to make education more engaging and requirements more sensible, so that borderline kids like our son don’t struggle with focus in the first place.

Hoosh.

Not sure about this. Everyone has different responses to medication, and different responses at different ages. By your own admission, the medication didn’t have much effect outside of a heightened self confidence, indicating either you never had the disorder to begin with (and admit this later in the episode), or it was so low in the scale, it barely registered.

That’s great. It means you weren’t the target for the medication, and it didn’t do much - nor should it have. Ultimately though, this whole episode comes across as “I didn’t get any benefit despite maybe/but probably not having the condition, so the medication is bad because big pharma.”

As someone diagnosed late in life, I wish I could’ve started on amphetamine based treatment far earlier. While it does assist with focus, more than anything, it helps with emotional regulation and reduction in anxiety, helps my memory, helps me to slow my brain down to take in one thing at once, and limits constant noise in my head. It also helped me build routines that wouldn’t have exist without the drug.

It has (quite literally) saved my marriage, my career, and in several ways, my life.

Adderall (and amphetamine treatment in general) have been proven to have some of the highest treatment efficacy of any psychotropic medication classifications existence. This research is widely available, and makes me wonder how many scholarly articles on the medication were actually read and considered prior to this episode, or if there was substantial cherry picking going on.

If you want to actually provide a balanced presentation on the treatment of ADHD, please look up Dr. Russel Barkley, a neuroscientist with some of the most prevalent and preeminent ADHD research over the last two decades to counterbalance the ultimate message of “it’s pharmaceutical advertising.” His impact has been tremendous, and can’t be understated.

Are the medications for everyone? Absolutely not. Even people with ADHD. Is ADHD over diagnosed? Absolutely, but that’s multiple different issues including a lack of high quality, affordable mental healthcare.

Instead of being properly diagnosed (a $2k process for myself, $3k for the pediatric versions for my son - neither covered by insurance), people are turning to online automated prescribing services, or other low quality, low cost providers who can make money off the medications (much like your second doctor).

Maybe this response is a knee jerk reaction to the podcast, but labeling amphetamine based treatments “speed” and meth throughout the episode and even in the title does little to help with the stigma, and presents the views pretty clearly.