Am I the victim of an international sushi scam? (Plus some thoughts on podcasting)

This week on the show, a deeply personal investigation

Hello Searchers,

Happy Saturday. We have a new episode for you and I wrote at length about trying to make sense of this bleak year in podcasting and especially the cancellation of Heavyweight, one of my favorite shows. That’s at the end of the email.

First, our story this week: it’s an investigation, which sent us on the trail of the walu-walu, also known as escolar, also known as the ex-lax fish. It gives you very terrible GI distress if you eat more than a small amount of it. Are New York City sushi sellers sneaking it into sushi?

Our path leads us deep into the shadowy world of black market fish sales, and sends us hot on the trail of the infamous ex-lax fish.

Plus, we look back to antiquity for the first-ever recorded emergency podcast.

Further reading for this episode

Here’s the 2021 Oceana study of fish fraud in NYC, which is pretty jaw-dropping.

An escolar recipe, if you like to live life on the edge (worth it for the comments, if nothing else).

The current home for the Chaos Dwarfs Online.

Bleak news this month in the world of podcasting.

More layoffs, more show cancellations. Just when you think this industry can’t sink further, it does. More shows have, at least for now, been canceled.

I wanted to use this space to talk about one of those shows, and to talk about how it feels to work in this industry right now, from my perspective.

Heavyweight is, justifiably, many people in audio’s favorite show. If you had to justify our medium’s existence, you might point to Heavyweight.

Jonathan Goldstein, Heavyweight’s host, was a medium-sized hero of mine before he was my friend. We got to work together at the same podcast company. And in those early years, it felt very special. At one point, he and I even lived on the same block. I used to go to his house where we’d drink this kind of bourbon he liked. The bourbon was called Old-Granddad. It really burned. Not everything Jonathan did made sense.

I always felt like I was getting away with something when we hung out. I’d started listening to Jonathan’s stories a decade before, in college, around 2006. He was the person who did stories at This American Life that didn’t sound like anybody else’s. I loved the This American Life house style, but I also loved that Jonathan was always subverting it.

If you want to hear what might be the prototypical example of the low-stakes quest form, a genre that has been turned into entire successful shows in the gilded age of podcasting – listen to the Little Mermaid. One of the absolute greatest radio stories ever recorded, which predicted so much that would copy it. It was broadcast in 2002.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/203/recordings-for-someone/act-one-13

The thing about Jonathan, even then, was he could really fucking write. Radio writing doesn’t have to be elevated. It can be functional. And sometimes it’s best left functional. A common radio writing sin is to reach, to strain, to end up flat on your own ass. Radio is brutally unforgiving to purple prose. I won’t hyperlink to an example here. You’ve probably heard it. I’ve definitely written it.

Jonathan could pull off literary radio writing though. He could give you strange combinations of feelings with his pieces. High, low, funny, sad. He also had a perfect deadpan.

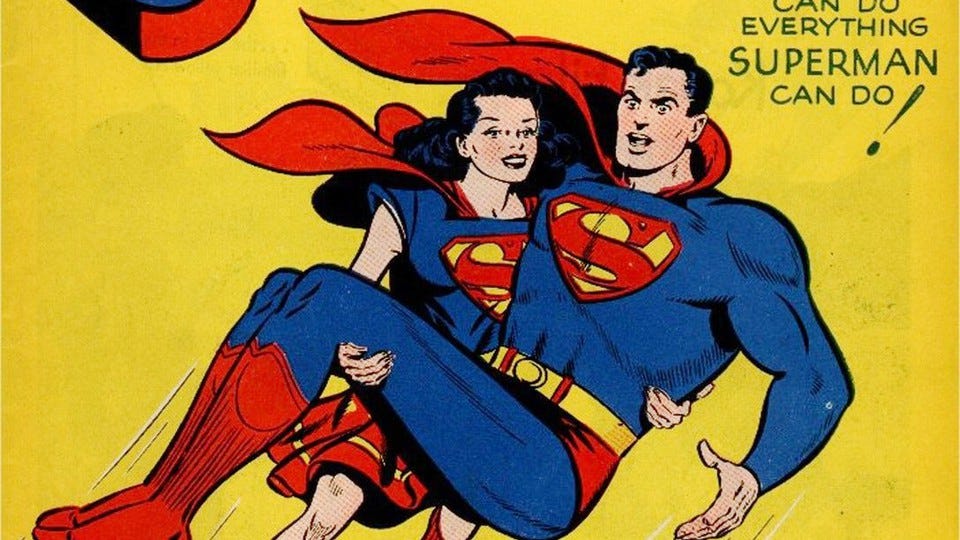

Once, he wrote this short piece of radio fiction from the perspective of a guy who is dating Lois Lane. The guy has a suspicion that Lois Lane, despite what she says, still isn’t over her ex. Her ex is Superman.

The narrator keeps confiding his troubles to this friend of his, a man named Clark Kent. Clark listens, he sympathizes. You, the listener, suspect he might not be the right person to talk to about all this. The story’s not just funny, it’s tender. And Jonathan does it all with such efficiency.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/198/how-to-win-friends-and-influence-people

I don’t know how Jonathan’s brain comes up with stuff like this. I’ve never asked him. It felt like a violation of our friendship to acknowledge how much I admire him, which is maybe a mistake.

In the first half decade of my radio career, when he was a faraway Canadian genius who I admired, I was obsessed with figuring out how to make work like his. But there were very few outlets where you could publish that sort of work. This American Life worked with freelancers, sometimes. So did Radiolab. I was too intimidated to pitch those shows. The week I started as a freelancer, someone told me there was one other show I could pitch called Weekend America, which folded a week after. Tough pickings.

Before money came into podcasting, we had this system called radio, which had two big narrative shows. And in that system, at any given moment, it felt like there were maybe two available jobs, neither of which paid well enough to live without three roommates.

During the radio era, I had three roommates. Jonathan had a show in Montreal called WireTap. A small-staff, small-budget weekly. A weird, brilliant show that mixed real interviews and made-up stories, interviews with Jonathan’s friends, literature, comedy, sadness.

WireTap was really good, but when the gilded age of podcasting showed up, one of the exciting things it augured was actually the end of WireTap. Jonathan Goldstein was coming to the company where I worked.

He was going to get the budget and the time to make something more precious, something that could come out less often. He could spend more time on reporting and polish. That show was Heavyweight. It was, it is singular.

I feel weird talking about that show and this person in the past tense, so I'm going to stop now.

I strongly expect that around this time next year, there will be new work from Jonathan and his team. I believe that like every year, they’ll somehow exceed their previous season.

So I'm just going to switch here to the part where I talk about how weird and confusing this all feels. To be a part of an art form that has been such a mindfuck to work in for the last ten years.

You can look around at 2023 and you can say that money ruined podcasting. There’s evidence for that idea, but I don’t think it fully captures what happened.

From my perspective, an influx of fast money had some weird effects on podcasting. Some of them: bad. Some of them: strange. A few of them: good.

I feel cursed sometimes, like I’m the only person who remembers that while the dumb money funded a lot of dumb shit in podcasting, it also funded a lot of the shows that I, at least, loved. Heavyweight was one of those shows. Another was even dearer to my heart though: the late, great Prince Harry’s Spotify Royal Spectacular.

Prince Harry had this way of conducting an interview that was so moving, so ahead of its time that– OK, not really. The point is, the dumb money came, some beautiful stuff got made, some dumb stuff got made, and now the tide’s gone out.

My understanding of the economics of ad-supported podcasting in the last decade went like this: take a show’s audience, multiply it by how often it publishes. Multiply that by your best guess for ad revenue per episode (crime shows are notoriously low, tech shows are high).

(audience x frequency x ad rates)

Whatever number you wind up with, you can subtract from that number the show’s overhead. The lion’s share of overhead is always staff salaries and benefits. If the number’s positive, you have a healthy show. If it’s negative, you don’t.

(audience x frequency x ad rates) - (overhead) = show

My theory for building a show in the last era was very basic. Keep costs down in the beginning (small staff, no traveling) and publish a lot. Hope and pray people pay attention to the show during its barebones stage. Try to ensure the show gets better over time, or at least keeps changing. Take big swings when you can afford to, they can sometimes earn you more audience. As you build an audience, you’ll have more budget. You can use the bigger budget to either increase headcount, increase reporting resources, or decrease publishing load.

Avoid the temptation to do any of these things too much, because ad rates could always drop and bork your math.

It’s fashionable (but in my opinion, also correct) to say that there was “too much growth” in the last era of podcasting. I don’t know what other people mean when they say that. What I mean when I say that is that there were a lot of shows that started out with large budgets and would have needed to reach large audiences almost overnight to succeed.

If you want the example that everyone loves to tease, sure $20 million dollars for a show with the royals that rarely comes out and isn’t widely listened to is the obvious knee-slapper.

But there were other shows with strange economics. These shows worried me.

When some people at some companies behave in economically unusual ways, other people at other companies think “hey, maybe they’ve figured something out!” And they copy them. I think when enough people do that, you get a bubble. When the bubble pops, you get what we have now.

These days, when a show ends, I find myself trying to do back-of-the-envelope calculations estimating their numbers. I can see their headcount and guess at salaries. I can see their publishing frequency, I guess at their audience size.

I do that because I want to believe that the industry I depend on still makes a cold kind of sense. But because I have a habit of doing that math, it means that sometimes, when a show I liked ends, I don’t feel as upset as other people. It still bothers me, but I can understand why it happened.

The Heavyweight cancellation throws even my cold, mathematical heart though. Yes, I believe the show will return. But the cancellation upsets me. Not just because I care about the people who make it, or because I care about the art those people make. It upsets me because I don’t understand it.

Heavyweight is a small, disciplined show with a large, devoted audience. It publishes seasonally, sure. But if the numbers weren’t there, they must have been close. I look at this Heavyweight moment and I tell myself that my hopeful theory here is that the same companies that grew too fast are now cutting too fast. But the alternative is that maybe I don’t understand this industry as well as I thought I did.

No one in podcasting knows what’s going to happen next, and people are worried.

You can find, if you look for them, chin-strokey pieces and posts about how the end of this podcast or that company is evidence for someone’s grand unified theory of art and commerce.

These pieces and posts sometimes leave me a little bit mystified. They’re often light on reporting and heavy on certainty. They’re not for me.

But, there are other conversations happening, some of them offline. Most weekends, I find myself on the phone with someone else who is trying to make their show work in this cruddy year.

Those conversations are less filled with certainty or blame. In the absence of an observing crowd, the tone is quieter. It’s people asking each other questions: You good? What have you figured out? What’s working? What’s not? What’s your best theory for how we survive the next two years?

This weird artsy-casual, sometimes-reported narrative audio we love to make and listen to … to what degree can we actually make it work, as a business?

I don’t know. Search Engine is a series of half-erased sketches towards some answers. I am sharing my notes here in case they help anyone.

Here’s what we believe, right now:

-we do not want to be owned by a large institution

-companies that aren’t being blasted with lots of fast money can be more deliberate about their culture

-we want the team to stay small

-we don’t want to depend entirely on ads

-we are publishing more than in the past, but the work is still deeply rewarding in all the ways that matter

-the listeners are still here, and the relationship with them is even more important now

Beyond that, I am / we are mainly just making educated guesses.

Just between you and me: Search Engine is growing, but it’s not profitable. We are hustling to try to get there, but it's a ways off, and we may not succeed. Our team gets paid because every month we get an advance from our ad-sales partner. We have a budget that’s good until July. After July, we’ll see.

Surviving in podcasting right now means working without a clear vision of the future. That sounds scary, until you remember we’ve never had a clear vision of the future. We just sometimes thought we did. And now we know that anyone who promises certainty is a swindler, a blowhard, or on deadline.

That said … here’s my prediction for the future. I don’t think Jonathan Goldstein is leaving podcasting. And honestly, however dumb our industry gets, I expect the next Jonathan Goldstein will find their way to podcasting. We are not entirely rational actors.

In the meantime, thanks for listening. I’m glad you’re here.

PJ

One of the most fun things I ever got paid to do was interview Jonathan Goldstein about his Little Mermaid story. Not surprisingly, he’s as good at explaining the thinking behind his work as he is at everything else he does. Sharing for any Jonathan fans who like to geek out on this kind of stuff: https://niemanreports.org/stories/annotation-tuesday-jonathan-goldstein-and-the-little-mermaid/

Heavyweight is one of those shows where, after I’ve heard an episode, I save it to listen to it again with my family. Just yesterday my 20-year-old daughter and I listened to “Rob” (the one where Rob remembers breaking his arm, and his family is convinced it’s a false memory) on a long drive. We were shrieking with laughter, but the show also led to a good conversation about memory, family legends, and the struggle to have our version of our history believed.

My husband and I recently listened to the episode about the man whose coach hugged him after his mom died and it changed the course of his life, making him a more open and loving person. I was in tears at the end, when Alex told him, “I love you man.”

It takes courage in our cynical, irony-laden culture to tell stories about deep, authentic, and sometimes uncomfortable feelings like the ones in Heavyweight. Every episode is a tiny masterpiece. I was so sad to hear that the show was canceled, and I hope with all my heart that you are right, PJ, and that Alex and the crew will be back very soon.